I. Introduction

In this introduction I want to give you an overview of what people now know about ancient China, its history and literature. Then I can provide a short introduction to the mechanics of the Chinese language. These sections may seem irrelevant to the Dao, yet I would ask you to get through the first few paragraphs of each section. Of course continue to read if the subject proves interesting. The terminology I bring up now will provide useful in later web pages.

At the end of this section is a table of selected Chinese characters. I have chosen them because they have meanings which do not always translate well and/or they have significant meanings within the Daoist texts. Oftentimes I will use their transliterations in the middle of my English text as if they were English words.

Ancient Chinese History

Dynasty Names

If you were lucky enough to learn anything about ancient China when going to school in a Western country, you learned the names of its ruling dynasties. Here is a list of the first few. I have included my dates for the beginning and ending of these dynasties.

- Xia (circa 1900 - 1600 BCE)

(Officially the beginning date for the Xia is given as 2070 BCE, but there are reasons to think that is wrong.)

- Shang (1600 - 1046 BCE)

- Zhou (1046 - 250 BCE)

This dynasty is divided into

- Western Zhou (1046 - 771 BCE)

- Eastern Zhou (771 - 256 BCE)

and the Eastern Zhou is divided into

- Spring and Autumn period (771 - 400 BCE)

- Warring States period (400 - 256 BCE)

- Qin (221 - 207 BCE)

------------ (the burning of the books, 215 BCE) ------------

- Han (202 BCE -)

Our discussions will mostly stay within the first three dynasty periods, the Xia, the Shang and the Zhou.

Traditional Chinese History

The first true history of China, the Shi Ji (史記)was written in the early Han dynasty. It listed all the rulers back to the beginning of the Xia dynasty, and it even included references to several venerable folks who ruled prior to the Xia:

- Yao (堯)

- Shun (舜)

- Yu (禹)who supposedly spent twenty years fighting the Flood.

In the nineteenth century Western scholars considered the Flood, the Xia and the Shang dynasties to be myths as there was no physical evidence to corroborate the narrative in the Shi Ji. At least for the Shang dynasty those scholars proved to be totally incorrect, for in the early twentieth century Chinese scholars discovered the remains of the last Shang dynasty capital at Anyang, along with thousands of oracle bones. The inscriptions on the bones confirmed precisely the names of the Shang kings as noted in the Shi Ji.

However the question remained: how much of the Shi Ji's earlier history might actually be true? Archaeologists now have putative sites for the location of the early Shang and the Xia capital cities. I am going to assume these locations are correct. In any case the archaeological finds do provide a good idea as to what the Xia and Shang cultures were like. And geologists have tantalizing evidence regarding the how and the when of the Flood.

Literary sources

Like the Old and New Testaments, old Chinese texts have gone through a lot of revision through history. One must be cautious whenrying to determine the original meaning of any of these books.

The Oldest Literature

Scholars generally agree there are only three surviving old Chinese books which contain text written in Early Ancient Chinese. This is the language on the oracle bones or on bronze inscriptions from the Western Zhou (1200 - 800 BCE). The three are

- Shang Shu or Book of Documents (尚書) (portions of some speeches)

- Yi Jing or Book of Changes (易經) (some entries)

- Shi Jing or Book of Poetry (詩經)(some longer sections)

The fact that all these texts are partially old and partially newer shows that they have all been compiled over a period of time, probably over hundreds of years. All of them are said to have been edited by Confucius around 500 BCE. It will be up to us to carefully discern from these documents what ideas come from the original writers and what ideas were added by editors later. Given its poetic nature I think the Shi Jing is less likely to have been extensively edited; therefore I will rely on it more often as a meaningful source of Western Zhou thought.

Other histories

Confucius also is thought to have compiled a work named The Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Period (Zuo Zhuan, 左傳). The Zuo Zhuan is based on the events of the early Eastern Zhou dynasty (700 - 500 BCE) as recorded by the kingdom of Lu; it is written in the style of Late Ancient Chinese. The stories in this document can be very colorful and sometimes allegorical. It can be difficult to know, however, whether the beliefs presented by persons in this history reflect the thoughts of their times, or the later thoughts of the compiler.

Dao De Jing

The Dao De Jing probably was compiled in the time of Confucius, say 400 - 500 BCE. It is attributed to Lao Zi. The Shi Ji says Lao Zi was a southerner from the state of Chu who worked in the Zhou government. At some point he left his job and went west. Leaving the state of Zhou, he paid the entrance fee for the state of Qin by writing the Dao De Jing. Continuing west he "was never to be seen again."

painting "Lao Zi on an ox passing through Hangu Pass" Zhang Lu (Ming dynasty, 1300 - 1500 AD)

Present day Lao Zi statue at Hangu Pass

The Dao De Jin has 81 short chapters in 2 sections. The language among the chaptrers varies, suggesting some of them were written as early as 800 BCE, others after 500 BCE. The text passed down to us through tradition (the received text) dates from 100 AD.

In addition to the received text the Dao De Jing now has been found in two tombs, with two full texts at Mawangdui (buried 180 BCE) and a partial text at Guodian (buried 280 BCE). The differences among these texts will be a topic of discussion later.

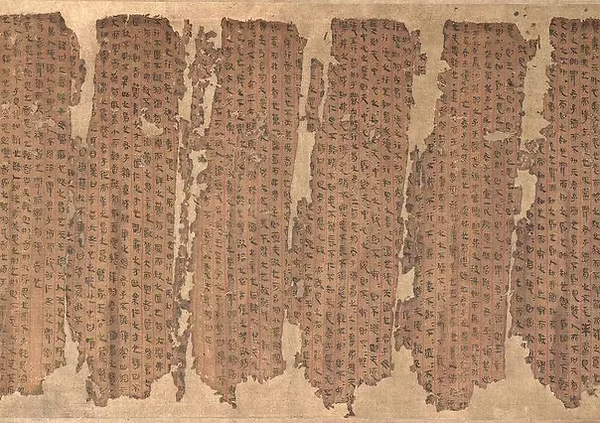

Silk Manuscript of Dao De Jing Unearthed From Tomb of Prime Minister Li Cang (? — 185 BC) — Mawangdui Museum of Hunan Province

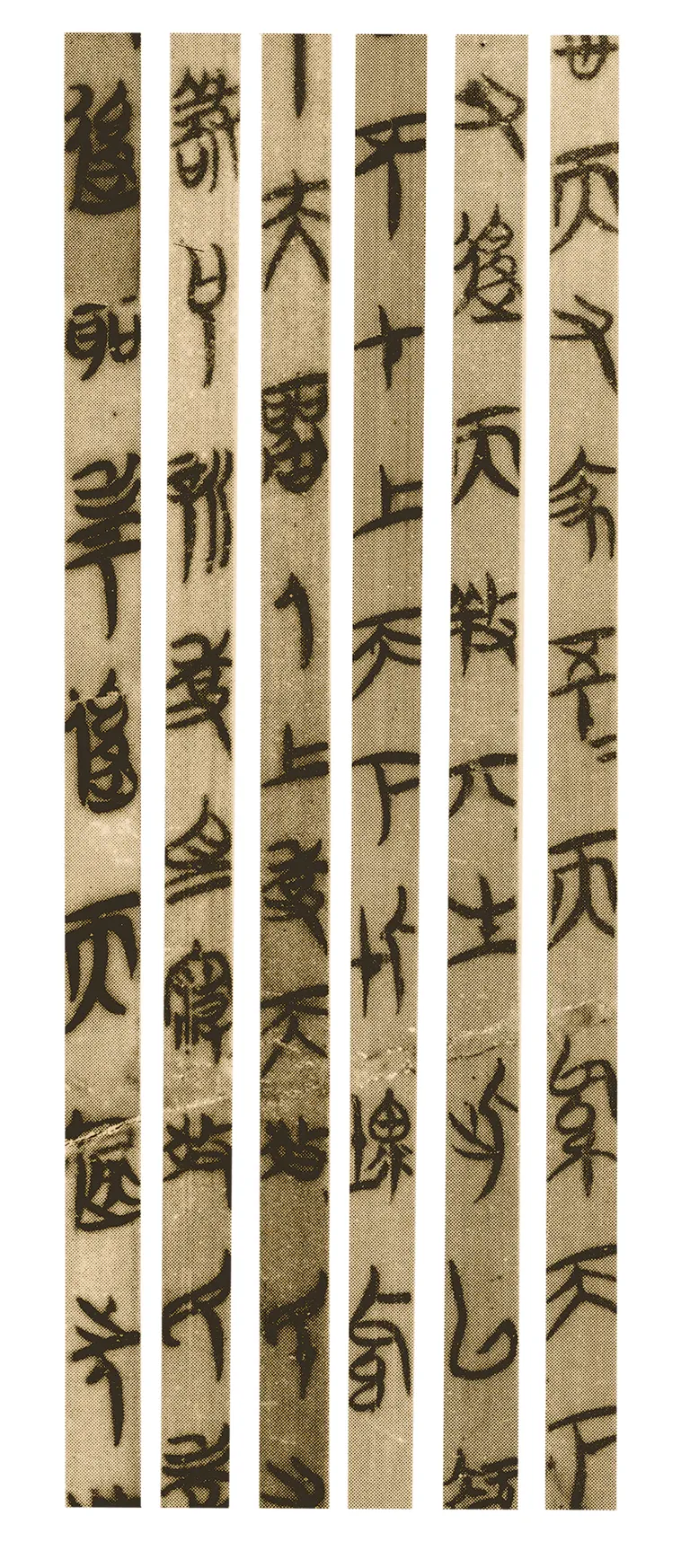

A few bamboo strips from the Guodian Tomb

Zhuang Zi

Zhuang Zi is named after its putative author, Zhuang Zhou. The Shi Ji stated that he was from the small state of Meng, and was known through his writing to be witty and sarcastic; he had once refused an offer to work as a minister in the state of Chu. The book attributed to Zhuang Zhou shows a variety of style among its 33 chapters; Chinese scholars early on separated out 7 "inner chapters" as worth more attention. As its text refers to both Confucius and Lao Zi often, it must have been written later than the Dao De Jing. Educated guesses place its writing around 260 BCE. Our received text dates from 300 AD.

Inscriptions on Chinese Bronzes

Like the texts found in tombs, bronze sacrificial vessels with written inscriptions are enormously helpful in reconstructing Chinese history. As the artistic style of these vessels evolved over time, a bronze vessel may be dated on the basis of its style alone, even when no dates are present in its inscription.

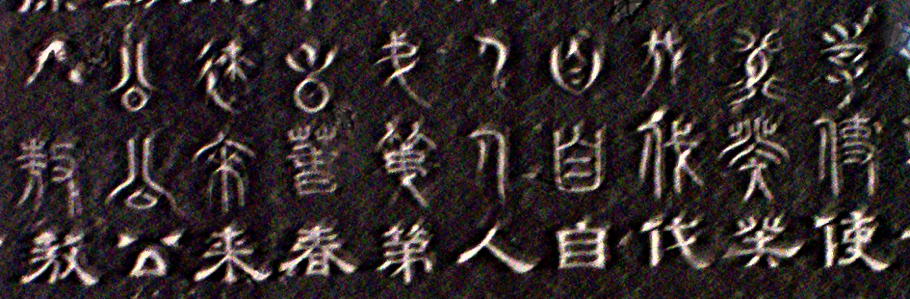

Shiqiang Pan with a long inscription inside the bowl

Portion of inscription inside the Shiqiang Pan

The vessls from the early (Western) Zhou period may have insciptions up to 400 characters long. These inscriptions allow an unimpeded view of what the people of that time actually thought. I will rely on them as an important source when tracing early Zhou political and religious ideas.

An Aside about Chinese writing and phonetics

Chinese writing depends on characters. Each character represents one syllable worth of sound. In Ancient Chinese a single character corresponds well with what we call a word (in modern Chinese words often require two or more characters).

The ancient bronzes show that writing was vertical, with lines of characters proceeding from right to left. When ancient Chinese was written as a banner, it would be read from right to left as well. In the twentieth century there has seen a general shift to horizontal writing, read from left to right. Exceptions remain in more traditional locations.

San Francisco Chinatown gate. The plaque in the middle now would be written " 天下為公 "。

The style of writing Chinese changed along with the writing instruments and sufaces used. In both Early and Late Ancient Chinese the characters were drawn differently from now. Paper was only invented around 200 BCE, so the brush and ink writing style had not developed.

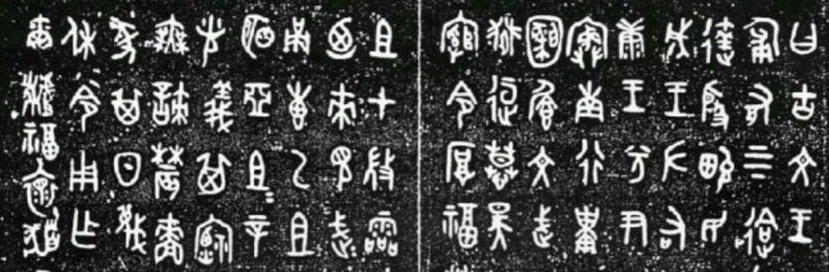

Portion of a stele showing three lines of identical text (Luoyang Museum)

Here is a Rosetta stone of sorts demonstrating the evolution of Chinese script. [I apologize for the blurry photograph; it was taken furtively as photographs were forbidden in the Museum.] The lines of text displayed above come from a monument carved about 600 AD. All three lines are the same text. The top line is written in seal script as would have been inscribed in bronze ca. 1000 BCE. The next line uses seal script as written on bamboo ca. 200 BCE. The final line is in clerical script, used after 100 AD until modern times,

Transcribing tomb documents and bronze inscriptions can be tricky. Scribes when copying any text might substitute a character that was different from but homonymous with the correct character. The way a character would be written could vary significantly from place to place, as there was no standardization of character writing before the Qin dynasty. As a result transcribing an ancient text into modern Chinese characters is a challenge. It usually takes several years of study and debate by a committee of scholars in China before a newly discovered document is released to be read by academic people in the West. Some early documents, when displayed in these web pages, may include corrections that Western scholars have proposed. It goes without saying that there can be heated disagreements about the words in these texts, let alone disagreements about translation.

An additional aside about phonetics

Many ways of writing Chinese phonetically have been proposed. Two are commonly in use in this country.

- Wade Giles

Wade and Giles were missionaries in the nineteenth century. Their phonetic rendering of Chinese reflects pronounciation in the lower Yangzi River region, and it uses the symbols like apostrophes that were popular among nineteenth century linguists. It is an awkward system for writers. However it is still in use in Western writing, and to a much lesser extent in Taiwan. in Wade Giles phonetization the Dao De Jing is written as Tao Te Jing, Beijing as Peking.

- Pinyin

was developed in the 1950s by mainland Chinese linguists as a compact way of rendering phonetics using only the Roman alphabet. It bases its phontetics on standard North China plain Mandarin. Sometimes its uses the Roman alphabet for sounds different from what a Westerner might expect (e. g., x for a soft sh, q for a soft ch).

Pinyin has proven quite popular, even Taiwan formally adopted it in 2009. I will use pinyin exclusively in these pages.

Traditional versus simplified characters

In addition, there are now two different ways to write modern Chinese characters.

- Traditional Characters. Once standardized in the Han dynasty Chinese characters remained unchanged for two millenia. Currently they are still commonly used in Taiwan and to a lesser extent Hong Kong. However most publications displaying Ancient Chinese texts use them. Of course anything published before 1960 uses traditional characters. Like most Westerners in the 1960s, I learned Chinese with traditional characters. I prefer them when discussing ancient China. .

- Simplified Characters. Developed along with pinyin transcription in the 1950s, they have replaced traditional characters in mainland China and Singapore. I will not be using simplified characters in these pages.

Appendix: Important Chinese Words

Here is a list of Chinese characters which I might refer to without translation. In this text I will write them capitalized using traditional characters and the modern pinyin transcription. This table includes the old Wade-Giles transcription and any simplified character versions of each character as well.

| Pinyin Transcription | Wade-Giles Transcription | Traditional Character | Simplified Character | Standard Definition |

| Dao | tao | 道 | path, way; to narrate, guide | |

| De | te | 德 | reward, blessing, grace. Later virtue | |

| Di | ti | 帝 | god, spirit. Later emperor | |

| Ling | ling | 令 | command. Also an early character for Ming (命) | |

| Ming | ming | 明 | brilliant, bright; clarity, intelligence | |

| Ming | ming | 命 | command, destiny, fate | |

| Ming | ming | 名 | name, fame; to name | |

| Qi | chi | 氣 | 气 | air; spirit, energy |

| Ran | ren | 然 | -ly, -ness | |

| Shang Di | shang ti | 上帝 | superior or higher god | |

| Tian | t’ien | 天 | sky, heaven | |

| Tu | t’i | 土 | earth, soil | |

| Wei | wei | 為 | 为 | make from something else; consider as, appoint |

| Wen | wei | 文 | first king of the Zhou dynasty; literature | |

| Wu | wu | 無 | 无 | there is no, without, non- |

| Wu Wei | wu wei | 無為 | 无为 | there is no wei; non-wei |

| Yi | i | 以 | to take, to use, with; in order to | |

| You | yu | 有 | to have; there is | |

| Zheng | cheng | 正 | a carpenter’s square; upright, true, square, correct | |

| Zi | zu | 自 | one’s self (as an adjective) |